My Famous Friend, Robert Blan

Originally Published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Robert Blan was proud of the girls in his life. He’d lean back in his seat, rest his crossed arms on his chest, and regale me with anecdotes about his daughters, Robin and Vinci, and his dear friends, Danica and Heather, pharmacists at Sherwood’s Drug Shop where he sipped coffee every morning for most of his life.

When I met him in August 2022, he bragged about all of them in a way that made me envious. Robin, Vinci, Danica and Heather are all adults, but I loved how he referred to them as girls, affectionately, fatherly. How wonderful it must feel to be one of his girls, I thought. I spent a lot of time with Mr. Robert, as I called him, over the following six months. He shared countless memories with me, and, along the way, Mr. Robert and I created some of our own.

I learned about Mr. Robert from my mom. She saw a friend’s Facebook post about an 89-year-old man who was the last remaining member of a long-standing coffee club. He sat alone at a table in a pharmacy every morning, drinking coffee, and chatting with passersby, said the post. Very familiar with my affinity for senior citizens, my mom knew this was a man I’d want to meet, and a story I would want to write. She told me about him on a Friday afternoon. I was sitting across from him the next morning.

Mr. Robert was friendly with all the customers at Sherwood’s, greeting them, exchanging niceties, and he was just as friendly to the new faces, including mine. We sat together at the small round table, his home away from home, and he told me the story of his life, chapter by chapter. While the article I wrote for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution focused on Mr. Robert’s relationship with Sherwood’s, I heard countless stories that, though they didn’t go to press, made an impression on me.

Mr. Robert moved to Buford as a child and never left. He married his high school sweetheart, Mildred, they raised two daughters, and he worked at Eastman Kodak for 35 years.

After he retired, he drank coffee every morning at Sherwood’s with a big group of friends, many of whom he’d known most of his life. He and Mildred used to take long drives that Mr. Robert timed just right, so Mildred could gaze upon the most beautiful sunsets.

A carousel of vivid images streamed in my head as he detailed story after story. It was a simple life, but it sounded extraordinary. There was joy, there was heartbreak, all narrated with conviction. He missed Mildred, who passed in 2011, he missed his coffee club buddies, most of whom had died, but he was one of the most content people I had ever met.

The world outside was bustling, anxiety the buzz word on everyone’s lips, but next to Mr. Robert, I felt nothing but calm. Time slowed as we talked, and I savored every second.

I had a handful of interviews with Mr. Robert and all his girls. They’d been so warm, welcoming me into the fold. Once the story was published, I wasn’t ready to say goodbye to any of them, so I didn’t.

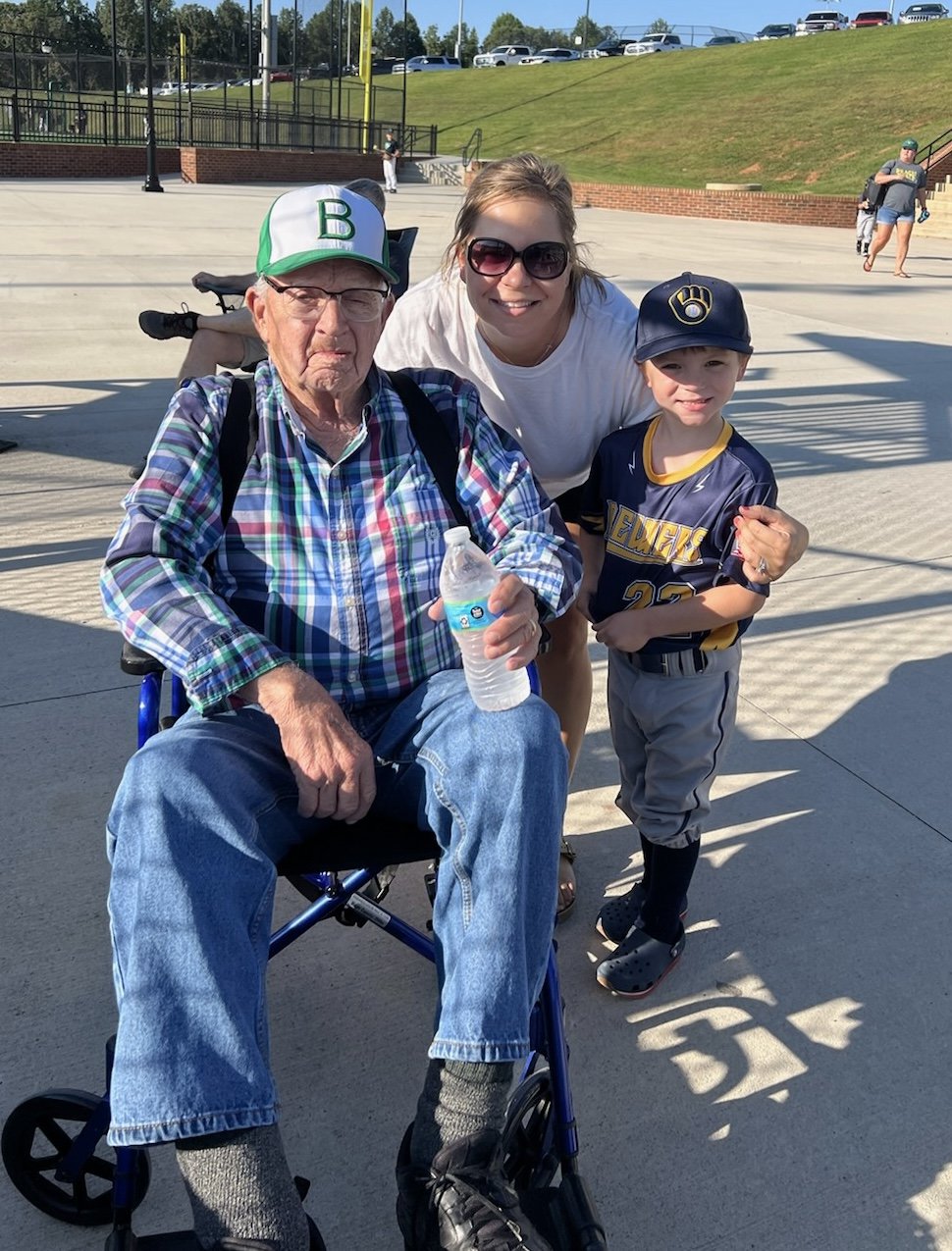

Vinci brought Mr. Robert to watch my sons’ youth baseball games, and I’d take my sons to the pharmacy to visit with him. In December I attended Mr. Robert’s 90th birthday party, which his daughters hosted at the pharmacy. I continued visiting him at Sherwood’s nearly every week. With his story displayed on the wall across from us, Mr. Robert and I sat, now side by side, my hand between his two, as he introduced me to customers as “the young lady who made him famous.”

After dropping my children off at school in March, I received a text from Danica. I didn’t read it entirely, but saw the words fall, hospital, and very bad. I immediately changed lanes and drove to the pharmacy. I rushed inside, still wearing pajamas, and Danica told me everything. Mr. Robert, who had recently experienced a couple ministrokes that exacerbated his dementia, walked out of his home in the middle of the freezing cold night, and fell in the road as he was heading who knows where. Doctors said his chance of survival was unlikely. Danica and I wrapped our arms around one another and sobbed.

A day later, I visited Mr. Robert in the hospital. It broke my heart to see the cuts and swelling on his unconscious face, to see his daughters with their tear-stained cheeks, but I was grateful to be by him once more, to lay my hand on his chest and thank him for his kindness, his influence, for the stories he shared with me.

I lay my head near his, close to his ear, hoping he’d hear me in his deep slumber. “I love you,” I said, words I felt since the moment I met him. I received a call from Robin 30 minutes after I left. “Dad passed. We think he was waiting for you.”

Days later I stood before a crowded room and eulogized my friend, Mr. Robert. I told everyone, as I told those he introduced me to at Sherwood’s, I did not make Mr. Robert famous with the AJC story. He was a legend all on his own, a salt of the earth, humble man who never wanted more than exactly what he had.

I recalled many of the stories he had told me, including the details of the canes he hand-crafted. More than once, he’d held up his cane in the pharmacy and walked me through his process, step-by-step. The canes were made of hickory from the grounds where he once hunted. “Ounce by ounce,” he’d say with authority, “hickory is stronger than steel.” Mr. Robert was like hickory. Better than one could ever fathom.

I visited Mr. Robert’s grave a couple of weeks later. I gave my respects to Mildred and took comfort knowing that, after years of missing her, he was with her again.

I continue to visit the pharmacy. I don’t sit in his chair. I can’t do that. I sit to the right of it, where I sat when he’d hold my hand, and I drum away on my computer, writing stories and remembering the one that led me to that very spot. It’s my hope to carry Mr. Robert’s torch in some small way, to be a friendly presence at his table in the center of his beloved pharmacy, grateful for simple pleasures, the friends behind the counter most of all.

I met Robin for coffee one afternoon, and, recently, the pharmacists and both of Mr. Robert’s daughters took me to dinner for my birthday. We laughed as we shared stories about him. “This would make dad really happy, seeing all his girls together,” Robin said.

I wish I had as much time with Mr. Robert as they had, but I’m so grateful for those six precious months. I had wondered how good it must feel to be one of his girls. Now I know.